Such is Life is a collection of very different short stories that will have readers longing for more – if they survive….

Ordinary people can do remarkable things when their worlds get turned upside down.

This collection of seven short stories and a novella began as something to do when insomnia called and the world was asleep; it took a motorcycle ride around the world to finish it.

“Such is life” are reputedly the final words of Australia’s famous folk hero, bushranger Ned Kelly, before he was hanged in 1880 - ironically on November 11, a day more recently dedicated to peace. Those words might be uttered by many of the people in this book too.

Despite only basic schooling, Ned penned a letter describing local law enforcement as "a parcel of big, ugly, fat-necked, wombat-headed, big-bellied, magpie-legged, narrow-hipped, splay-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords".

As insults go, that ranks at the top!

Fun fact: Ned’s life was the subject of the world’s very first feature film in 1906.

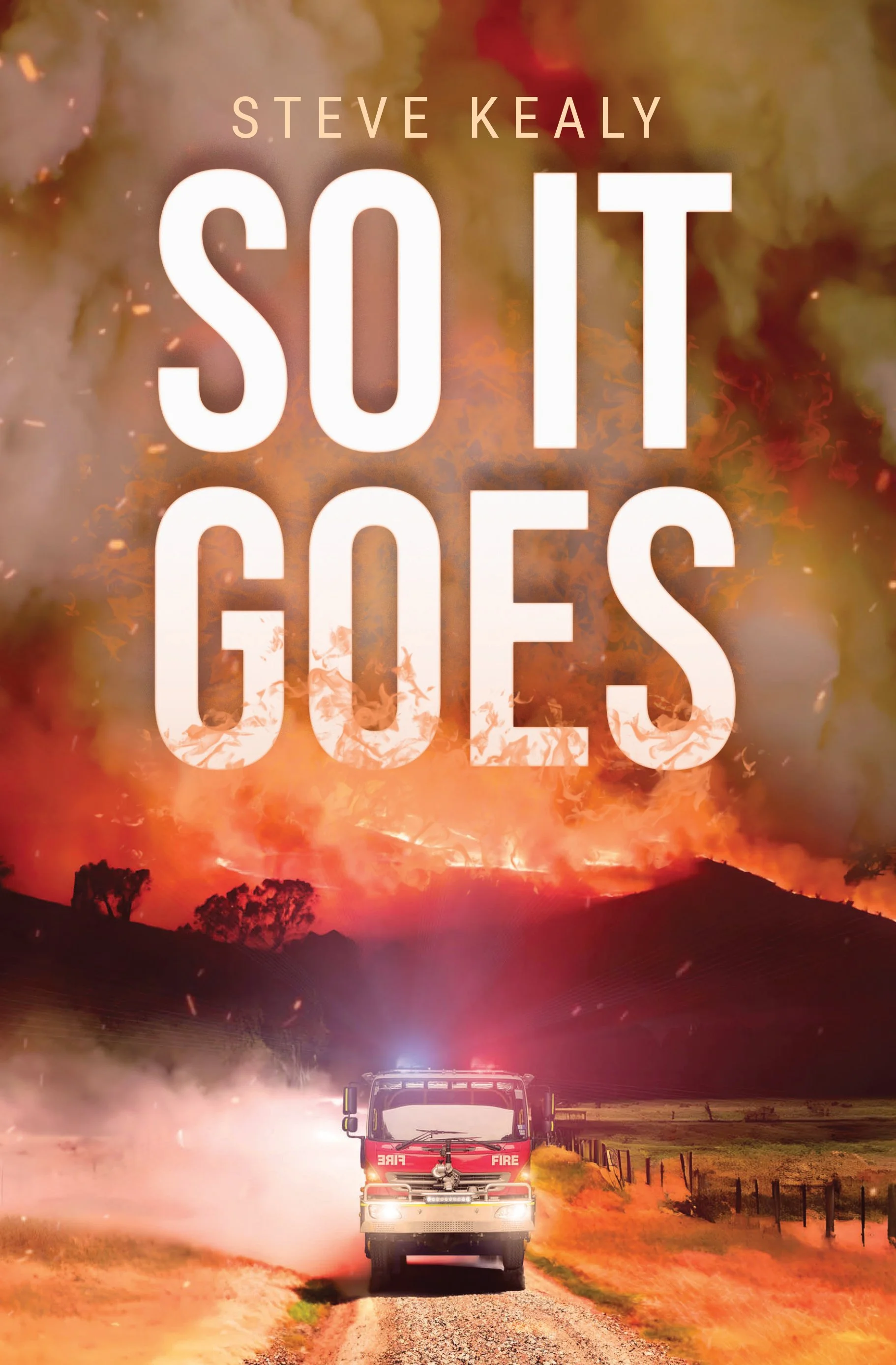

So it Goes

Not everyone survives.

This collection of Dark Fiction short and not-so-short stories covers the range of thriller, horror, mystery and suspense with tales of courage, loss, determination and decency.

With a mixture of realism and macabre surrealism, the reader is transported from a suburban coffee shop to a hidden jungle town, from the heart of a wildfire to a deserted rural road, from a hospital to a tribal village and to times and places not entirely of this world. The stories are told with a stark reality that puts you right there: you can smell the smoke, feel the fear and hear the desolation.

These stories will resonate with you for days after you’ve finished reading them.

Abruptly pulled out of a war zone to deal with problems back home, Devlin Moore travels to faraway Cape Town to find his missing mother. But is he already too late?

Armed only with an address and aided by his sassy cyber-savvy sister and two ageing strangers, Devlin is soon unravelling a web of crime and perversion in a country where bullets are cheap and life is cheaper.

As the body-count rises, Devlin realises his enemy is better-connected, better-resourced and well-hidden; he has to rely on luck, skill and rat-cunning to stay alive.

Readers of old-school operatives like Reacher, Milton and Bourne will warm to new-gen digilante siblings Devlin and Clarissa Moore, as they take on a network of evil with fingers in every dirty pie, in a story seemingly plucked from the headlines. And when it comes, payback’s a bitch!

Make sure you grab a copy of Cape Fire, the first salvo in this explosive new series, and look out for the hard and fast sequels, London Rising and Santiago Slide.

An elderly lady is donating to a poor African church – or is she?

Seemingly wrenched from today’s headlines, this fast-paced digilante thriller sees Australian SAS soldier Devlin Moore and his new girlfriend Rebecca sent to track down what seems to be a simple scammer, but their enemy is super-smart and hiding in a world Devlin doesn’t know or understand.

Not even Bec's lethal fighting skills or her uncanny language abilities can save them. Only Clarissa, computer Goddess on the other side of the world, can do that.

But is that enough?

Nothing, nowhere and no one are what they seem, as the pair are led to a grand London home that hides a string of dark secrets.

All the way to the explosive finale, there are twists, turns and tripping hazards aplenty. The pair have help from some unexpected places, but ultimately, it's down to Devlin alone to ensure the crims are shut down, in true Aussie style!

Hot on the heels of Cape Fire, the first salvo in this explosive new series, London Rising is the hard and fast stand-alone sequel. Keep an eye out for the eerily true-to-life Santiago Slide.

He doesn't speak the language, doesn't know what his enemy looks like, or where he's going…

A government employee ventures where he shouldn’t, and some secret files are stolen. To get them back before they are offered for sale on the Dark Web, SAS Corporal Devlin Moore finds himself in the Andes, where he's plunged into a web of evil over eighty years in the making.

Looted Nazi treasure, a mysterious woman and ghosts of the Disappeared are side orders in a haunting place where everything and everyone seems to have a value, and a price.

Devlin must withstand attempts on his own life and soon realises there's much more at play than a few lines of code.

With sister Clarissa bending anything connected to the internet to her will back home, the pair must trace and track a mystery thief who doesn’t know what he's stolen. Yet.

When Devlin lends a hand by doing what he does best, the unspoken global network of warriors kicks in, and he's offered unexpected help from an unlikely source. The results are earth-shattering!

The eerily true-to-life Santiago Slide comes hot on the heels of the explosive stand-alone novels Cape Fire and London Rising in the Devlin Moore series.

Want Something for nothing?

Join the mailing list for updates, backgrounds and new releases from South Morang's sharpest writer!

To send you the free, never-published short story Just One Shot, or the prequel to the Devlin Moore series Winged Stagger, click on the QR codes below:

Scan this code to receive a free short story along the lines of what you’ll find in my Dark Fiction collections!

Scan this code to receive a free short story prequel to the Devlin Moore digilante series - or click here: https://dl.bookfunnel.com/w2ekhzgau2

About the author

Born in Libya, Steve has lived in ten countries on three continents; now a rural area outside Melbourne is home, where he’s a volunteer fire-fighter, a veteran of more than 500 emergencies and several of the bigger fires of the past two decades; he’s a double recipient of Australia’s National Emergency Medal.

He’s also a volunteer Role Model ambassador for the Books in Homes charity, which gives primary school children books of their choice. In the past, he’s worked in gold and uranium mines, a nuclear power station, the army, the media, on radio and TV.

His shows have been seen in 35 countries, translated into several languages, and even used as TESL teaching aids.

A multi award-winning journalist, he has an MBA and is researching a PhD.

Defying Apartheid laws and death threats, he started the world’s biggest motorcycle charity event, The Toy Run, receiving thanks from Dr. Nelson Mandela. Now in its fifth decade, the Toy Run has benefitted over three million children.

Steve entered many classes of motorsport in cars and on bikes; after one international win, a few crashes, two broken necks and a huge amount of fun, he’s reluctantly stopped racing. Instead, he flies a Jabiru – an aircraft the size of a shopping trolley.

And he rides motorcycles, a lot – since he was 9 years old and living in Yemen, where he learned to ride.

In 2017, he rode over 45,000km (the distance around the world) through 16 countries on four continents. He’d do it again, in a heartbeat.